| |

THE EICHENTOPF FLUTE: THE EARLIEST SURVIVING FOUR-JOINT

TRAVERSO?

by Ardal Powell

Word count: 4000. Download size (text only): 30,000

bytes.

Author's note: This is an English version of "Die

Eichentopf-Flöte: die älteste erhaltene

vierteilige Traversflöte?", as it appeared in

Tibia 1/95, 343-50.

Abstract: A unique transverse flute by Johann

Heinrich Eichentopf (1678-1769) in the Bachmuseum,

Leipzig, has a strong claim to be considered one of

the earliest four-joint flutes to survive. Though

the instrument has been altered in order to raise

its pitch, this article describes a reconstruction

of its essential features. A successful reconstruction

seems to confirm that the sections have not been significantly

shortened and the bore of the flute is entirely original.

Characteristics of the bore at the central tenon-and-socket

suggest that an important reason for the division

of the three-joint flute into four in c.1720 was freedom

of access to this region. It is further suggested

that the division into four sections may have pre-dated

the addition of corps de rechange by a short

time.

1. INTRODUCTION

Johann Heinrich Eichentopf (1678-1769) was a wind instrument-

maker working in Leipzig from 1710 to 1749. Various

suggestions exist of a link between him and J.S. Bach,

including the fact that he delivered at least five instruments

to the court musical establishment at Köthen, probably

some time after Bach left service there.1

The list of surviving instruments by Eichentopf shows

that his workshop had a wide range, producing all members

of the oboe and bassoon families, recorders and brass.2 But only one traverso with the I.H. Eichentopf

stamp is known.3 This is an ivory flute in the collection

of the University of Leipzig, number 1244, located in

the Bachmuseum, Thomaskirchof, Leipzig. It was examined

and measured by Catherine Folkers and the author in

May 1992 and March 1993. Our thanks are due Dr. Winfried

Schrammek, the museum director, and museum staff for

access to the instrument and permission to publish this

report.

The museum catalogue states that the flute dates from

about 1730 and no later than 1749, that the upper middle

joint has been shortened by about 18mm, and that the

tenons of that joint and of the lower middle joint (or

heartpiece) have been altered.4 Despite the fact that its condition is not original,

the instrument deserves attention because of its unusual

proportions, its unique testimony to Eichentopf's work

as a flutemaker, and of course its possible closeness

to Bach. Furthermore as I will try to show, it has a

strong claim to be among the earliest four-joint traversos

in existence.

2. DESCRIPTION

The flute has some unusual features. The very finely

turned end- cap contains a screw-cork with its threaded

spindle projecting through the cap. The screw-cap rotates

on a tenon at the upper end of the headjoint, and this

tenon has grooves in it. The mounts at the sockets are

fitted on sleeves, so that an endwise view shows two

concentric thicknesses of material. The workmanship

of the ivory turning at the headjoint and heartpiece

sockets, while it is competently executed, is not of

the same quality as the very fine work of the original

parts of the endcap, and of the end of the footjoint.

In the workmanship of the footjoint it is quite easy

to see the two different hands responsible for the flute's

present condition: the mount at the socket, again fitted

on a sleeve as far as the ring which holds the key,

is not in proportion to the rest of the piece, and its

ornamentation does not relate in size and shape to that

of the outer ends of the flute. These discrepancies

in the style of turning5

together with the shallow depth of the heartpiece socket

suggest that the instrument has been shortened at the

mounts, rather than--or as well as--at the tenons as

the catalogue states, and that the work was done by

a craftsman of less skill and artistry than the original

maker.

In fact all the tenons connecting the pieces appear

to have been shortened. On the heartpiece, not only

the tenon but the actual sounding length at the bottom

of the joint has been altered: the facing where the

tenon begins is imperfectly executed, and since the

sixth hole is thus closer to the footjoint, the key--which

itself may well not be original--has been shortened

to make room for the finger to cover the sixth hole.

The sounding length of the upper middle joint gives

no sign of having been changed.

An original embouchure, with its center at about 199.7mm

from the present end of the headjoint socket, has been

drilled out and plugged, and a new, oval hole made in

the back side of the headjoint at 167.6mm. According

to the catalogue, a silver shield, lost between 1903

and 1925, was set into the ivory to cover the plug.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the flute is

its unusual bore (see Figure 1). Traverso bores in the

early eighteenth century generally have a more or less

cylindrical headjoint (though conical headjoints both

contracting and expanding are to be found), a generally

contracting conical mid-section (or two mid-sections

in the case of four-joint flutes), and a conical footjoint,

usually expanding.

The overall taper of the Eichentopf's bore is very slight

compared with most other flutes of the period. It is

also unusual, though not unique, in having two prominent

steps where the bore becomes larger, instead of gradually

reducing in size in the normal way.6

The first of these is at the intersection between the

bottom of the left-hand section and the top of the heartpiece,

where there is a dramatic enlargement. The second step

is at the beginning of the footjoint--whose bore continues

with the same contracting conicity as the two upper

joints, not flaring out again as is usual.

The overall taper of the Eichentopf's bore is very slight

compared with most other flutes of the period. It is

also unusual, though not unique, in having two prominent

steps where the bore becomes larger, instead of gradually

reducing in size in the normal way.6

The first of these is at the intersection between the

bottom of the left-hand section and the top of the heartpiece,

where there is a dramatic enlargement. The second step

is at the beginning of the footjoint--whose bore continues

with the same contracting conicity as the two upper

joints, not flaring out again as is usual.

3. RECONSTRUCTION

Almost certainly the instrument in its present, altered

condition does not sound as Bach may have heard it.

But curiosity about its original playing qualities made

an attempt to reconstruct the instrument seem worthwhile.

The changes were evidently made with the intention of

raising the flute's pitch to bring it up to the standard

of a later age, an all too common fate of obsolete one-keyed

flutes. The sounding length of the headjoint is made

more than 30mm shorter by the new embouchure; the changes

at the sockets also effectively shorten the tube. The

range of possible original dimensions for each of the

altered features is quite large, with a correspondingly

wide range of influence on playing qualities, given

the fact that alterations in bore, hole size, placement

and undercutting measuring 0.1mm or less can have a

transforming effect. Since no other traverso by Eichentopf

is known, there are no direct comparisons to be made,

and flutes having similar general proportions are extremely

rare. But at least Eichentopf's working period, 1710-1749,

helps us reduce the range of possibilities by ruling

out any features typical of later flutes. The unusual

length of the headjoint, seeming to derive from the

proportioning of the three-joint flute, also invites

comparison with models from the early part of the period.

The original embouchure must have been more or less

exactly in the same place as the hole made for the plug

which replaced it when the new embouchure was made.

If they shared the same center it would be 199.7mm from

the present end of the headjoint. But to judge from

the outer profile the mount seems to have been shortened

by about 8mm, and the depth of the socket increased

to compensate. Thus the sounding length of a reconstructed

headjoint would be 207.7mm. We would not expect to find

an oval embouchure, like the one the flute has at present,

on a traverso from the first half of the eighteenth

century; we can be fairly certain the original was more

or less round: not more than about 0.2mm larger from

side to side than from front to back. Embouchure size

rarely exceeds 8.9mm from front to back on well-preserved

specimens from before 1750. And holes as small as 7.5mm

in size are not uncommon on early examples. The most

probable original size would be in the middle of this

range, around 8.2mm, with diminishing likelihood for

dimensions up to half a millimetre larger or smaller.

The undercutting ought probably to match that of the

flute's fingerholes in their unaltered state: the first

hole could well be taken as an example since, as the

hole closest to the embouchure, its pitch would rise

more than any other hole's whan the flute was shortened

and there would be no need to enlarge it, so it is probably

in its original condition. The undercutting of the holes,

generally speaking, is slight to medium, and quite concave,

especially where the side walls join the front and back,

with slightly more undercutting one one side than the

other. The second hole has little undercutting on the

bottom side, the third and fifth holes do appear to

have been enlarged, though carefully, and the hole covered

by the key is very little undercut. The size and undercutting

of the fifth hole ought more or less to resemble the

fourth; and the size and undercutting of the third hole

can be determined--assuming for the moment that the

bore has not been altered--from the tuning of A and

G# in all three octaves, and of E'''.

It is inconceivable that the original endcap contained

a screw- cork device. With the embouchure in its original

position, there is barely room for the cork itself,

much less any auxiliary machinery to move it about--and

there is no sign that the top of the headjoint has been

shortened. What we can learn about the invention and

purpose of the screw-cork7 makes it improbable that the device was known

to Eichentopf or used on a flute without alternative

upper middle joints. The grooves in the tenon argue

for thread windings which would have held the cap in

place--this too quite inconsistent with its use as a

screw device.

Though both the tenons of the upper middle joint seem

to have been shortened, it does not appear that the

section's sounding length has been reduced. The headjoint

socket was probably deepened to give it strength after

the joint was shortened, so perhaps the corresponding

tenon, already 28.5mm long, has only lost a millimetre

or two of its original length. In the heartpiece, by

contrast, the large bore and small outside diameter

leave a wall too thin to allow the socket to be given

the extra depth, up to 10mm, one would expect. Thus

the tenon that fits it is left a rather stubby 16.1mm

long. The original heartpiece mount could have been

up to 30mm long instead of the 18.5 it is; a first attempt

at reconstruction showed that such a normal-length mount

gave a scale whose low notes were not satisfactory.

Further attempts suggested that the heartpiece mount

had been shortened by only 8mm; restoring this much

length gives the instrument a well-balanced scale and

a socket 20.5mm deep. The comparative shortness of the

resulting heartpiece mount (26.5mm) on the reconstruction

is warranted by that of another apparently early ivory

flute, the one by Scherer (Y14) in the collection of

Nicholas Shackleton, Cambridge.8 The key, shortened to a fraction over 52mm,

could not have been less than about 56.6 originally,

and if it reached to the bottom edge of the 6th hole--its

maximum practical length--the heartpiece must have been

at least 4mm longer at the bottom end than it is now.

So the total increase in length of the heartpiece would

be about 12mm, to give a new sounding length of 140.9mm.

With the flute restored to something like its original

length so that it will play at or slightly above the

pitch it was designed for, let us now consider the bore.

Is it in its original condition, or was it altered when

the pitch was raised? Reamer marks at the top of the

heartpiece or in the footjoint might indicate this,

but there is no sign of irregularity: the bore is quite

highly polished, and still shows an evenly-spaced pattern

of tiny striations such as would be left by a burr or

a small nick on the cutting edge of a reamer. Otherwise,

the only indication that the bore is or is not in its

original condition will be whether or not our reconstruction

of the flute works as well as an instrument made with

such evident skill and care ought to do.

One feature at least is an obvious alteration. The bore

of the top tenon of the left- hand joint has been crudely

enlarged with a knife or scraper. Here and in the places

where tenons have been shortened, the bore might tend

to expand or contract more or less in the same proportion

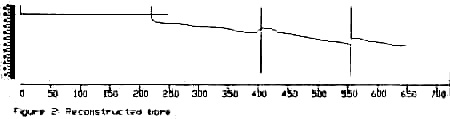

as before. A "reconstructed" bore is shown in Figure

2.

Our model having the dimensions suggested here plays

at 392--400 cps, depending on the player.9 The instrument has excellent intonation in all

keys (except that the hole under the key produces D#

rather than Eb), a good, even sound quality, and a quite

exceptional facilty in the highest register. Clues that

the instrument with its newly-restored dimensions works

as intended are that F''', a note that on out-of-condition

instruments is often difficult to obtain, is well in

tune and easy to play; and A''', another note which

sometimes seems reluctant to speak, can even be attacked

piano and played with a crescendo or a diminuendo. From

G' downwards, the first octave is strong and even in

quality, so that even the unusually low tessitura of

the G major trio-sonata BWV 1027 does not seem out of

place. Our model's playing qualities certainly do not

make it less suitable than any other pre-1750 instrument-type

for any of the cantata parts or solo flute music of

J.S. Bach.10 The unusual length of the headjoint, the shallow

conicity of the bore, and the general appearance, sound

and response of our model of the instrument are quite

similar to the Brussels I.H. Rottenburgh (Conservatoire

Museum No.2001, pitched at about a=400), copies of which

some performers are using today to play Bach. However

there are pronounced differences in tonehole spacing

and bore profile, as well as in wall thickness--they

are made of different materials--which distinguish the

two instruments no matter how similar they may be in

appearance11.

4. DATING

Whether or not this is considered an accurate method

or a convincing reconstruction of the Eichentopf flute

in its original condition, the model does at least confirm

that the bore is generally unaltered and the original

proportions must have been more or less as suggested

here. With this in mind, it will be necessary to reconsider

the catalogue's dating of the instrument at 1730 or

later.

Quantz, who has been followed by all subsequent authorities,

states that the three-joint flute was divided into four

about 1720 to allow changes of pitch by means of corps

de rechange.2

But if we consider flutes proportioned like the Eichentopf

and I.H. Rottenburgh, this explanation does not seem

entirely convincing. The upper middle joint of these

flutes is already very short, while they play at the

lower of two common chamber-music pitches.13 Upper middle joints more than a few millimetres

shorter would upset the visual proportions of the instrument

and bring the first tonehole uncomfortably close to

the tenon: even when the Eichentopf flute's pitch was

raised by a whole tone, the maker who did the work avoided

the usual course of making the upper middle joint shorter.

There is no indication that longer alternative sections

existed--indeed, if they did, their pitch would be exceptionally

low. It seems improbable, then, that this type of instrument,

which retains the general proportions of the three-joint

instrument and thus would seem to be very closely related,

was developed to accommodate corps de rechange.

The only practical way to shorten the sounding length

of such a flute by more than a few millimetres would

be to recast the proportions of the instrument's top

half so that the headjoint was shorter and the longest

middle joint, playing at the present pitch or slightly

below it, longer. Thus it would play at its present

pitch with the longest of a set of middle joints, and

shorter ones would give higher pitches. On surviving

instruments made after about 1720, and on all known

examples which actually have corps de rechange,

precisely this change in proportions has occurred. The

maker who raised the pitch of the Eichentopf followed

the same prescription by drilling a new embouchure,

effectively shortening the headjoint in relation to

the rest of the flute.

So if Quantz was mistaken, and the three-joint flute

was not divided into four to make corps de rechange

possible, why was it done? The unusual bore of the Eichentopf

flute provides a plausible, if somewhat surprising,

answer to this question. Eichentopf, or the flutemaker

who worked for him, clearly wished to make the bore

in the region of the fourth and fifth holes larger,

while leaving it undisturbed under the third hole. On

a three-joint flute this would be impossible, because

a reamer which cut a given diameter could not be used

beyond a point in the tube that had a smaller diameter.

The only effective method of making a bore like this

would be to divide the three-joint flute's middle section

in two, reverse the taper at the end of the first of

the new pieces and begin the second with a larger bore,

and this by itself is a perfectly valid reason, from

an instrument-maker's point of view, for making the

division. Such an innovation might have occurred to

any maker, of course, but it might not have seemed like

much of a novelty to one in a workshop specialising

in oboes, which have two main sections joined by a tenon

and socket in the middle.

We must also consider the possiblity that the bore of

the Eichentopf flute arose as a result of the division

of the three- joint instrument into four, not as its

cause; that makers only took advantage of the opportunity

to reverse the taper in the middle of the instrument

and to create large steps in the bore after flutes in

four joints (with corps de rechange) were already

common. But this hypothesis would require the assumption

that the three-joint flute was divided either for a

reason we suspect to be unsound, or for some third reason

which we do not know.

Surviving examples with Eichentopf/Rottenburgh proportions

are extremely scarce. Though drawing conclusions from

the random selection of instruments that have survived

the centuries is risky, the rarity of this particular

type might indicate that not many were made; that the

idea of providing interchangeable middle sections to

alter the pitch occured shortly after, and as a direct

result of, the appearance of the first four-joint flutes.

This would have provided an attractively simple explanation

for the division of the three-joint flute into four,

and the intermediate stage with its long headjoint and

short upper middle joint would quickly have become obsolete.

5. CONCLUSION

Our experience with the Eichentopf flute suggests that

it could be the unique survivor of a short-lived but

important stage in the development of the instrument:

the three-joint flute had been divided into four to

give the maker access to the central part of the bore,

but corps de rechange had not yet been supplied,

at least by this maker. Considering only evidence in

the instrument itself, which the construction of a successful

model shows to be unaltered, there is reason to suppose

that the Eichentopf traverso is among the very earliest

four-joint flutes to survive to the present, probably

dating from shortly before Bach's arrival in Leipzig.

NOTES

1Bruce Haynes, `Bach's

pitch standards: the woodwind perspective', Journal

of the American Musical Instrument Society XI (1985),

101. A full survey of woodwind-making in Leipzig during

the early eighteenth century is in Herbert Heyde, `Der

Instrumentenbau in Leipzig zur Zeit Johann Sebastian

Bachs', in 300 Jahre Johann Sebastian Bach ed.

Ulrich Prinz, Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1985

2Phillip T. Young,

Twenty- Five Hundred Historical Woodwind Instruments,

New York: Pendragon Press, 1982, s.v. "J.H. Eichentopf".

3Eichentopf may

have made instruments sold by the Leipzig dealer Hirschstein

(see Paul Hailperin, `Three oboes d'amore from the time

of Bach', Galpin Society Journal XXVII (April

1975) p.26). Thus three other flutes, all in ivory,

could be by Eichentopf: the Hirschstein No. 13 in the

Musikhistoriska Museet, Stockholm; the Hirschstein flûte

d'amour in the Dayton C. Miller Collection (DCM

1267) and a similar one listed by Sachs in Sammlung

Alter Musikinstrumente bei der Staatlichen Hochschule

für Musik zu Berlin, Berlin: Julius Bard, 1922,

col. 256. The Miller instrument, while less well-made

than the Leipzig flute, shares some of the distinctive

bore characteristics noted below.

4Herbert Heyde, Flöten:

Musikinstrumenten-Museum der Karl-Marx Universität

Leipzig, Katalog, Band 1, Leipzig: VEB Deutscher

Verlag für Musik, 1978, p.84 and the illustration

in Table 9.

5One other traverso

with mounts turned in this style is known: a boxwood

instrument by Palanca, No. 851 in the Dayton C. Miller

Collection. It is finely made and the style of turning,

though unusual, is quite clearly deliberate.

6Some other instruments

that have a large step between the upper middle joint

and the heartpiece are: ivory Beukers, Haags Gemeentemuseum

Ea 414 (1933); ivory Bizey, Paris Conservatoire 439;

boxwood Schuchart belonging to Stephen Preston; boxwood

Denner recently acquired by Konrad Hünteler. The

first two instruments also have a step from the bottom

of the heartpiece to the top of the foot. I am grateful

to Rod Cameron for generously sharing data from his

studies of these flutes.

7An overview of this

subject is in Ardal Powell, "Science, Technology and

the Art of Flutemaking in the Eighteenth Century," The

Flutist Quarterly XIX.3 (Spring 1994), 33-42. [See

technology.php3 in this directory]

8Illustrated in Phillip

T. Young, `The Scherers of Butzbach', Galpin Society

Journal XXXIX (September 1986), Plate VIII.

9The model made for

the purposes of this study was in an artificial ivory

material of cast polyester resin. Ivory was avoided

for two reasons: it would have made transporting the

model from New York to Leipzig for comparison with the

original in March 1993 illegal under the Convention

on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES),

and it would have provided stimulus to the ivory trade,

though small, of a kind conscientious wind instrument-makers

are presently trying to avoid.

10See Ardal Powell with

David Lasocki, `Bach and the Flute', Early Music

23.1, 9- 29.

11Another flute with

similar proportions, in ivory, by Johannes Scherer Junior

(Butzbach: 1664-1772) or possibly Georg Henrich Scherer

(Butzbach: 1703- 1778), is No. 153 in the Vleeshuis

Museum, Antwerp, illustrated in [J. Lambrechts-Douillez],

Catalogus van de Muziekinstrumenten uit de versameling

van het Museum Vleeshuis, Antwerp: Ruckers Genootschap,

1981, p.63.

12Quantz, Versuch

I.9. The earliest datable four-joint traverso known

to me has unfortunately not survived to the present:

an ivory instrument by Thomas Boekhout (Flanders: 1665-1715)

was catalogued in 1922 by Sachs as No. 2678 in what

is now the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung

in Berlin, but has since been lost.

13See Haynes, `Bach's

Pitch Standards'.

|